Yoga. It’s a practice long associated with improving peace of mind, balance and strength – but of course, it’s also riddled in Hindu spirituality and culture (most classes begins with a “Namaste”).

While it’s practiced by many people of faith, or no faith at all, all over the world for its health benefits, an Irish Bishop this week has questioned whether it’s something that Christian children should be engaging in at school.

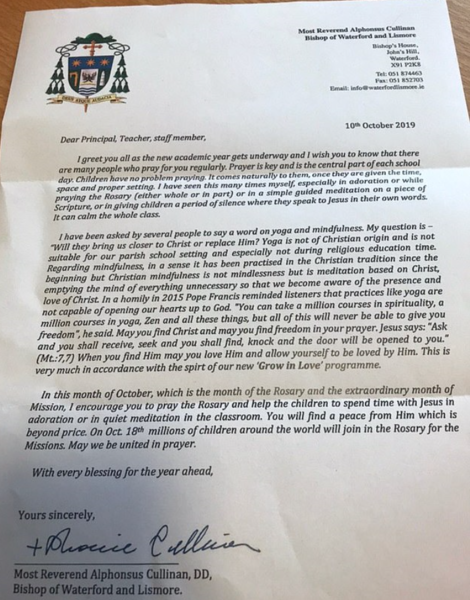

Writing to a board of Catholic schools in Waterford City and County, Ireland, Bishop Alphonsus Cullinan explained he wants yoga, something he describes as an overtly non-Christian practice, to be banned. In its place, he encouraged teachers to “help the children to spend time with Jesus in adoration”.

“I have been asked by several people to say a word on yoga and mindfulness,” the Bishop wrote. “My question is: ‘Will they bring us closer to Christ or replace him?’

“Yoga is not of Christian origin and is not suitable for our parish school setting. Mindfulness, in a sense, has been practiced in the Christian tradition since the beginning, but Christian mindfulness is not mindlessness but meditation based on Christ, emptying the mind of everything unnecessary so that we become aware of the presence and love of Christ.”

But with schools under increasing amounts of pressure to find new ways for children to get in touch with their emotions, be spiritual and find time to be calm, more and more are turning to yoga and mindfulness – including those which are Christian in practice.

“I teach in a Christian school but we practice mindfulness with all of our children,” says Pete Watts, a religious education teacher. “It’s not necessarily from a spiritual perspective but we believe it’s important to help children to manage their minds, and the mindfulness helps.”

Pete, who is also a youth leader at his church, believes that as long as you are clear on the heart behind such activities, children in faith schools should be able to practice yoga freely – as any mindfulness, faith based or not, is better than no quiet time at all.

“It may seem controversial, but I’d say that any meditation can be what you make it and depends on what heart you have behind it,” he adds. “It depends on the individual doing the practice and what they believe.

“Of course, yoga is spiritual, though not Christian. But if it is delivered to children in line with Christian teachings and beliefs in a setting such as the schools Bishop Cullinan is speaking to, it’s up to the young people to decide whether or not they take that spiritual aspect on board.”

For the Bishop, just lining up the teachings of Christ with the moves of yoga wouldn’t be enough. He goes on to quote Pope Francis, who in 2015 reminded his listeners that practices like yoga are fundamentally and at their core “not capable of opening [your] hearts up to God”.

“Giving children a period of silence where they speak to Jesus in their own words; it can calm the whole class,” the Bishop instead suggests. “I encourage you to help the children spend time with Jesus in quite meditation in the classroom.”

In contrast, Molly Heery, a primary school teacher and youth leader, suggests that while it’s important to recognise yoga’s history as un-Christian, children shouldn’t have to be limited to just activities that overtly “open their hearts to God”.

“Biblically we know and are taught to spend time with Jesus as much as we can, but it’s also known that we should and often do worship God in whatever we are doing,” she explains. “Whether I’m walking down the street, making a sandwich or doing yoga, if you know Jesus, you’re doing it in the glory of God. Through this mind-set, every activity becomes what you make it.

“At its core, yoga is a Hindu practice and holds connotations with that faith. But, as long as you’re clearly explaining to children where it comes from and crucially why you are doing it – in this case as a form of calming exercise and not necessarily worship – it can be done. Children can then make their own minds up about how they feel about it.

“Sometimes I get told not to teach Harry Potter to my Christian children because of its links with witch craft and magic, but that doesn’t stop me, a Christian woman, from doing so and appreciating it as a piece of literature. I strongly believe that if you avoid teaching children about opposing views, you risk them becoming intolerant.”

Pete agrees. Despite his faith, he admits that he always allows his children “to come to their own decisions” rather than expecting them to meet and agree with him. Because of this, he feels removing yoga would be “indoctrination”, and may leave young people confused when they are faced with such practices as adults.

“I always allow my children to make their own decisions about Jesus because I trust that God will speak through me and will work in whatever way needed,” he adds. “I’m always happy for my students to be exposed to lots of different arguments and activities to keep them informed of all the options before they form their opinion.

“From my experience as a youth leader, when you stop children from making their own decisions on what they believe about different practices, it causes problems in adulthood – when they’re faced with new things, often they can’t justify their faith and are left in crisis over their religious identity, having not formed their own mind early on.

“If you allow them to explore things like yoga, which is linked with another religion but is also just a great form of relaxation, you allow them to make that choice. You can’t indoctrinate them into pursuing Jesus as then it’s not genuine faith. For it to be effective Christian meditation, they have to choose to do so themselves.”

What do you think? Should we dissuade our children and young people to take part in practices like yoga?

Jess Lester is deputy editor of Premier Youth and Children’s Work.