Without warning, your hands have begun to tremble uncontrollably and you clench your fists tightly so that no one notices. Countless thoughts spike through your mind: ‘Did I leave the oven on?’ ‘I can’t do this job’, ‘When are people going to notice I’m a fraud?’, ‘I can’t do this job’. You struggle to catch your breath again as you try valiantly to calm yourself. You feel so weak, pathetic and petrified that you are about to be found out

If you recognise THESE FEELINGS, you aren’t alone. The above is a description of one of my panic attacks a few months ago. I know exactly how you feel . .

Generalised anxiety disorders affect around four per cent of the population, with a further ten per cent suffering from occasional panic attacks. In anxiety disorders, perhaps more than many other disorders, we see that the physical and the emotional are inextricably linked: anxiety presents in very physical symptoms, including heart palpitations, shortness of breath, and panic attacks, as well as the psychological symptoms such as rumination and hyper-vigiliance. The fear and exhaustion that a panic leaves in its wake is all too real; although the perceived danger doesn’t exist, you are left reeling as if it does. Yet all too often we mistake the disorder for a normal human anxiety which can protect us.

Anxiety in and of itself is vital to protect us, helping us to flee danger and fight any threats which we face. The language does these disorders a disservice. We all get anxious sometimes, and can all remember times when we might have felt panicked. The same can rarely be said for other illnesses; no one feels ‘a bit diabetic’ do they? Our proximity to feelings of anxiety makes acknowledging that some people are completely controlled by them all the more difficult. Disorders are far removed from the normal experiences of sadness and anxiety which weave their way through everyone’s lives at one point or another.

Sometimes I get a little worried that I’ve left my hair straighteners on and will return from work having burned the house down. There is a modicum of usefulness in this as it helps me to turn them off and keep my belongings safe. But that fleeting thought is almost unrecognisable compared to how I have felt when my anxiety disorder was raging and the thought of getting on a bus filled me with terror.

Defining anxiety

Theologians Jongsma and Peterson describe anxiety disorders in the following way; what’s particularly useful here is that they differentiate between those worries which are a natural part of life and anxiety:

‘It would be best to understand anxiety as excessive worry about life circumstances which have no factual or logical basis and persist on a daily basis for a significant period’

An anxiety disorder is not in the normal range of emotions; it is what happens when emotions fall through the looking glass and are warped by illness. The fight or flight instinct which is so useful when we are in life-threatening situations can be painful and embarrassing when it is triggered by something as simple as a phone call. The sleep which can refresh and restore us is instead used to torture, at first withheld completely and then unleashed making even the simplest of tasks near enough impossible through the fog of exhaustion.

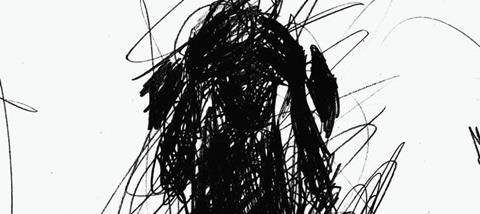

I like to think of anxiety disorders like the Devil’s Snare plant which entangles Harry, Ron and Hermione in Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. JK Rowling describes Hermione watching Harry and Ron:

‘she watched in horror as the two boys fought to pull the pl ant off them, but the more they strained against it, the tighter and faster the plant wound around them’

So often it can feel like this both for those suffering, and for those who are desperately trying to help. The harder you fight to free yourself from the thoughts alone, the tighter they wind themselves around you.

The fight or flight instinct can be painful and embarrassing

Real Christians don’t get anxious

The Devil’s Snare has another weapon for us Christians. This weapon is the unspoken belief that to struggle with anxiety is somehow a reflection on the health of your relationship with Jesus. The scriptures which can bring comfort are used to argue that Christians should be immune to mental health problems:

‘Do not be anxious about anything, but in every situation, in prayer and petition, with thanksgiving, present your requests to God.’ Philippians 4:4-6

So as Christians we shouldn’t be anxious because it’s a sin, right? Wrong. These verses are not a pronouncement that feelings of anxiety are sinful, but rather act as biblical CBT (Cognitive Behavioural Therapy), reminding anxious hearts and minds to lay their anxious thoughts at the foot of the cross of Christ. The language Paul uses in the verse that follows is military in its language. He says that the peace of God guards our hearts, a reminder that we can call out to the father and ask him to protect our hearts and minds against anxiety.

C.S Lewis wrote this in his Letters to Malcolm:

‘Some people feel guilty about their anxieties and regard them as a defect of faith. I don’t agree at all . They are afflictions, not sins. Like all afflictions, they are, if we can so take them, our share in the Passion of Christ’

It is tempting to think of mental health problems as contemporary problems, and yet we can see examples of anxiety in the Bible. More often than not, anxiety sits alongside shame and they feed off one another. Adam and Eve fled from God after they’d sinned, feeling the shame of their mistake and the sudden awareness of their nakedness.

Guilt and shame are the lifeblood of anxiety and part of our ministry both with our colleagues and our young people is to point always to the grace of God ruling over the shame of disorder. We are not afraid to acknowledge the Fall in physical injury or environmental disaster - so why are we so afraid to acknowledge its effect on the mind? There is still an ongoing debate concerning what causes anxiety, but we do know that early life experiences can adversely affect levels of depression and anxiety as can genetics and social factors.

we need to tackle the stigma of mental illness in our communities - and that means being honest when we are struggling

Speak Out

When I was at my most unwell, having panic attacks on buses and unable to trust in any kind of future, I felt an overpowering sense of shame. I could not lift my head in worship times and I believed myself to be bad for the kingdom of God (after all, it’s hard to share the good news when you’re crying all the time). I didn’t feel able to participate in communion and I could barely pray. I was utterly convinced that the gospel truth was for everyone except me. Reading passages such as the ones described above did not bring a heightened awareness of God’s presence, but taught me to be honest with God. I read Luke’s account of Jesus praying to his Father in Gethsemane until the words blurred before me. If the Son of God could be honest with his Father about the depths of his pain - then what was stopping me being honest?

Honest about my anxiety.

Honest about my feelings of abandonment.

They also allowed me to be honest with those around me. If I could lay my darkness before God then I could lay my darkness before those who loved me, and that honesty broke through some of the shame as I heard my story in a different way for the first time. I was unwell - but that didn’t make me a bad Christian or a bad person.

Sadly, one of the things that prevents people from feeling able to be open about their mental health condition is the undeniable existence of stigma. A staggering 87 per cent of participants in the 2008 Time to Change survey said they felt stigma had had a negative impact on their lives. If we are going to best care for those with anxiety and depression, both youth workers and young people, then we need to tackle the stigma of mental illness in our communities and that means we need to be honest when we are struggling. It means we need to talk as openly in our churches about mental illness as we do about physical ailments.

It also means that we need to be honest about what is hurting. When I used to have time off school or work to cope with yet another ‘bad brain day’ I would usually claim that it was because of my asthma. Struggling lungs seemed to be far more valid than a struggling mind.

I want to see a change. I want to be part of raising a generation who can be open about their struggles and not fear a backlash. Anxiety disorders, in whichever way they present themselves, are enough of a burden to bear without the added difficulties of stigma and pressure to stay silent.

So let’s step up and take care of ourselves and our young people by dragging the Devil’s Snare of anxiety into the light. In the story, the light and warmth of the fire loosens the ties for Harry and Ron. What a beautiful parallel with the light that God gives us through the life and death of Jesus.

What now … for youth workers

See your GP - certain chemicals and hormones can have a significant effect on your mood, so get yourself checked.

Maintain your boundaries - when you’re struggling yourself, it’s really important to stick to your boundaries both when working pastorally with young people and with your work and life balance.

Take care of your physical health - an apple a day can keep the doctor away and making sure you get enough sleep and exercise is proven to boost your mood.

VOCABULARY

Generalised Anxiety Disorder: Persistent feelings of anxiety without a cause, or disproportionate to the cause which disrupt normal life.

Panic Disorder: Regular and recurring panic attacks characterised by nausea, sweating, palpitations, feelings of dread or trembling.

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: Cyclical thought patterns including unwanted intrusive thoughts (obsessions), anxiety, feeling forced into certain behaviours to control the anxiety (compulsions) leading to a temporary relief from symptoms before the cycle begins again.

Listen to those who love you - let them take care of you!

Be honest - with God, with your family and with your colleagues.

What now… for young people

Address mental health issues in your youth programme - pray for mental health services together.

Encourage young people to talk openly with someone they trust.

Seek medical advice from a GP or mental health professional, if it is interfering with everyday life.

What now… for church leaders

Pray - a somewhat obvious starting place, but pray with and for your staff team regularly.

Get informed - check out websites such as www.mindandsoulinfo.org, www. thinktwiceinfo.org to see how you can best support a youth worker struggling with mental health issues.

Be observant - if you notice your youth leader is struggling, encourage them to take a break or seek help.

Be open - when we are honest about our own struggles, it can enable others to speak out.

Preach it - don’t shy away from tackling passages that deal with emotional health: the Psalms are a great place to start.

Rachael Newham (nee Costa ) is the founding director of ThinkTwice and a graduate from the London School of Theology.